A site audit revealed the client had 147 categories and 892 tags for a blog with 340 posts. Most

categories had one or two posts. Hundreds of tags had exactly one post each. Google Search Console

showed thousands of indexed pages—far more than their actual content—because every category and tag

created an archive page. Most of those archive pages were thin content that diluted the site’s

overall quality signals.

WordPress categories and tags seem simple on the surface—just ways to organize content. But every

taxonomy term creates an archive page that search engines index and evaluate. Poor taxonomy

decisions create duplicate content issues, thin archive pages, and diluted search authority. Many

publishers create categories and tags reactively without strategy, leading to exactly the mess I

found on that client’s site.

This guide explains how to structure WordPress taxonomy correctly from the start and how to fix

existing problems without losing SEO value. You’ll understand the fundamental difference between

categories and tags, avoid common mistakes, build an effective category structure, and use tags

strategically.

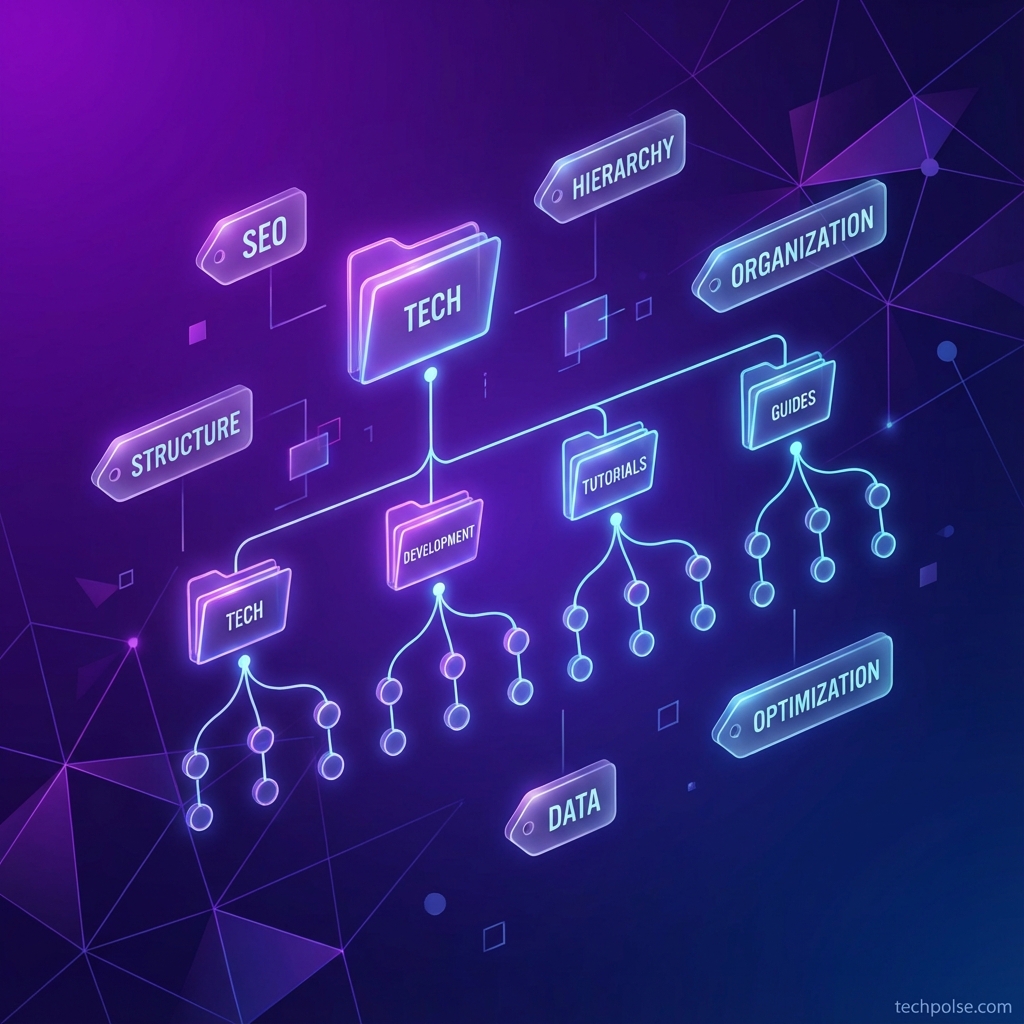

Understanding the Fundamental Difference

Before restructuring your taxonomy, understand what categories and tags actually do in WordPress and

how search engines interpret them differently.

Categories: Your Content Pillars

Categories provide hierarchical organization for your content. Think of them as the main sections of

a magazine or the departments of a newspaper. They answer the question: “What is this article about

at the highest level?”

Categories support parent-child relationships. A “Technology” category can have children like

“Software,” “Hardware,” and “Mobile.” This hierarchy creates logical content groupings and enables

URL structures that reflect content relationships.

Every WordPress post must have at least one category. If you don’t assign one, WordPress applies the

default category (typically “Uncategorized,” which you should rename or configure appropriately).

This requirement means categories are essential structural elements, not optional metadata.

Visitors expect categories to appear in navigation. They represent major content groupings that users

browse intentionally—”Show me all your WordPress articles” or “What do you have about SEO?” Category

pages become destination content themselves.

From an SEO perspective, category archive pages often accumulate significant authority. They contain

multiple related posts, receive internal links from navigation, and target topical terms. A

well-optimized “WordPress Tutorials” category page can rank for valuable informational queries.

Tags: Topic Descriptors

Tags provide flat, non-hierarchical associations between posts and specific topics. They’re more

granular than categories, capturing specific subjects mentioned in posts. Tags answer the question:

“What specific topics does this article cover?”

Tags have no parent-child relationships. Each tag is independent and equally weighted. This flat

structure means tags work differently for navigation and SEO than hierarchical categories.

Posts don’t require tags. Using zero tags is perfectly valid for many content strategies. Tags should

add value, not exist for their own sake.

The primary value of tags is connecting posts across different categories. A “JavaScript” tag might

appear on posts in both “Web Development” and “WordPress” categories, helping readers discover

related content they might otherwise miss.

How Search Engines See Archives

Both categories and tags generate archive pages that search engines crawl, evaluate, and potentially

index. A category page lists all posts in that category; a tag page lists all posts with that tag.

From Google’s perspective, these archive pages are content pages like any other. They have URLs, they

contain content (post excerpts or full content), and they get evaluated for quality and relevance.

This is where taxonomy decisions become SEO decisions.

A category archive with 50 relevant posts provides genuine value—it’s a curated collection on a

topic. A tag archive with one post provides no value beyond the post itself; it’s thin content that

wastes crawl budget and potentially dilutes site quality signals.

Common Taxonomy Mistakes

Understanding what goes wrong helps you avoid these issues on your own site. These mistakes are

extremely common, even on otherwise well-run publisher sites.

Too Many Categories

New publishers often create a category for every topic they might ever cover, resulting in dozens of

mostly-empty categories before any significant content exists. “I’ll write about AI, blockchain, web

development, mobile development, cloud computing, cybersecurity…” — each becomes a category with

one or two posts for years.

Categories with minimal content create thin archive pages. Google may view these as low-quality

doorway pages that exist for SEO manipulation rather than user value. Even if not penalized, they

certainly don’t help.

A good benchmark: each category should have at least 10+ posts to justify its existence as a

meaningful content grouping. If you can’t imagine reaching that threshold within a reasonable

timeframe, the topic belongs as a tag or subsumed under a broader category.

Start with 3-5 broad categories covering your core topics. Add new categories only when content

volume justifies them. It’s much easier to split a busy category than to merge empty ones.

Overlapping Categories

Creating “Technology,” “Tech News,” and “Tech Reviews” as separate categories seems logical but

causes confusion. Where does a technology news article that includes brief reviews belong? Probably

all three, which means the same post appears in three nearly-identical archive pages.

Overlapping categories split related content across multiple archives, reducing the authority of

each. Instead of one strong “Technology” archive with all relevant posts, you have three weaker

archives competing for similar queries.

The solution is using parent-child relationships or consolidating overlapping categories. Make “Tech

Reviews” a child of “Technology” rather than a sibling. Or recognize that “news,” “reviews,” and

“tutorials” are content formats, not topics—and tag for format rather than categorize.

Duplicating Categories as Tags

Some publishers create tags that mirror their category structure. A post in the “WordPress” category

gets a “WordPress” tag. This creates two archive pages—/category/wordpress/ and /tag/wordpress/—with

virtually identical content.

Search engines see two URLs with essentially the same posts listed, which can be interpreted as

duplicate content or at minimum dilutes whatever signals either page might accumulate.

Tags should complement categories, not duplicate them. If the tag name matches an existing category,

don’t create that tag. The category archive already serves that purpose.

Tag Explosion

The most common taxonomy mistake is tag explosion—adding many unique tags to every post without

considering whether those tags will ever accumulate multiple posts. Publishers treat tags like

hashtags, inventing new ones constantly based on whatever the post mentions.

With liberal tagging, a site can easily accumulate thousands of tags over time. Most will have one or

two posts. Each creates a thin archive page that provides no value beyond the posts themselves.

Worse, these pages consume crawl budget. Search engines spending resources on thousands of

single-post tag pages have less budget for your actual content. Site quality signals can suffer from

the proportion of thin pages to substantial pages.

Use only established tags that appear on multiple posts. Delete or noindex tags with fewer than 3-5

posts. Better yet, create a controlled tag vocabulary and only use predefined tags.

Building an Effective Category Structure

A well-planned category structure improves user navigation, strengthens SEO, and scales gracefully as

your content library grows.

Start with Content Pillars

Before creating categories, identify the 3-5 major topics that define your editorial scope. What

subjects will you cover extensively? What expertise do you bring? These become your content pillars,

each represented by a top-level category.

Balance breadth and depth. Categories should be broad enough to contain multiple subtopics but

focused enough to represent a coherent content area. “Technology” might be too broad (unless you’re

a general tech publication); “PHP Array Methods” is too narrow.

Plan for volume. Each category should realistically accumulate 20+ posts over the next year. If you

can’t envision publishing that much on a topic, it’s probably too narrow for a category—use tags

instead.

Consider your audience’s mental models. Category names should match how your readers think about

topics. If everyone in your space talks about “SEO” but you use “Search Engine Optimization,” you’re

creating unnecessary friction.

Using Hierarchy Effectively

Parent-child category relationships create logical content groupings without multiplying top-level

navigation items.

Create child categories when a topic has distinct subtopics that warrant separate browsing paths. A

“Web Development” category might have children for “Frontend,” “Backend,” and “DevOps”—each

substantial enough to justify its own archive and navigation entry.

Stick to two levels maximum. Parent and child is sufficient for almost any site. Three levels

(parent, child, grandchild) creates overly complex navigation and deep URL paths that suggest poor

information architecture.

Child categories need content volume too. Don’t create child categories for just 2-3 posts. Either

the subtopic belongs as a tag, or those posts belong in the parent category until volume justifies

subdivision.

Category Names and URLs

Category naming affects both user experience and SEO. Names should be clear, consistent, and

keyword-aware.

Use natural language that visitors understand. “Getting Started” is clearer than “Onboarding

Resources.” “Tutorials” beats “Educational Content.”

URL slugs should reflect how people search. The display name can be friendly and complete, but the

URL slug should be concise and keyword-informed. “WordPress Tutorials” displays nicely but

/wordpress-tutorials/ works better than /complete-wordpress-tutorial-collection/.

Pick a naming convention and apply it consistently. Decide on plural versus singular (Categories? or

Category?), with or without articles, and stick with it across all categories.

Category Descriptions

WordPress allows descriptions for each category. Many themes display these at the top of category

archive pages. Even if your theme doesn’t display them, SEO plugins often use them as meta

descriptions.

Write unique, useful descriptions for each category. Describe what content readers will find, what

value the category provides, and what makes your coverage distinctive. These descriptions can rank

category pages for relevant queries.

Strategic Tag Usage

Tags add value only when used consistently and with purpose. Random tagging creates more problems

than it solves.

Create a Controlled Tag Vocabulary

Rather than inventing tags on the fly, create a controlled list of approved tags. This list

represents your recurring topics—subjects you cover repeatedly that readers might want to follow

across categories.

Review your existing content and identify genuine recurring themes. What specific technologies,

concepts, or approaches appear in multiple posts? These become your tag vocabulary.

A tag should only exist if at least 3-5 posts will use it. Fewer posts means the tag is too

specific—either generalize it or don’t create it.

Document your vocabulary. Keep a reference list of approved tags so authors use consistent

terminology. “JavaScript” not “JS” or “java-script.” “Email Marketing” not “Email” or “Newsletters.”

Tags Per Post Guidelines

Aim for 3-5 tags per post. This provides useful cross-referencing without over-tagging. Every tag

should represent a major topic in the post, not a passing mention.

If a keyword appears once in a 2,000-word article, it’s probably not a major topic that warrants a

tag. If the reader expected that topic based on the tag archive, they’d be disappointed by the

minimal coverage.

Some posts legitimately don’t need tags. If no established tags apply, don’t create new ones for a

single post. Zero tags is fine when nothing fits.

Tags vs. Categories Decision Framework

When deciding whether something should be a category or tag, ask:

Will this have 10+ posts within a year? If yes, category. If no, tag or nothing.

Would users browse this directly? If yes, category. If it’s more for discovery, tag.

Does it cross other topics? If it appears across multiple categories, tag. If it defines a distinct

content area, category.

Is it hierarchical? If it has natural subtopics, category. If it’s a flat descriptor, tag.

SEO Configuration for Taxonomies

WordPress creates archive pages for every category and tag. These pages need proper SEO treatment

like any content page.

Archive Page Optimization

Using your SEO plugin (Yoast, Rank Math, etc.), add unique meta descriptions to each category

archive. Generic descriptions or no descriptions waste ranking opportunity.

If your theme supports it, add introductory content to category archives. A paragraph explaining what

the category covers, what readers will find, and why your coverage is valuable provides unique

content that differentiates the archive from a simple post list.

Ensure paginated archive pages handle SEO properly. Modern SEO practice relies on self-referencing

canonicals rather than rel=”next/prev” (which Google deprecated). Each paginated page should

canonicalize to itself, not page one.

Strategic Noindexing

Not every archive page deserves indexing. Strategic use of noindex prevents thin content from

diluting site quality.

Consider noindexing all tag archives. If your category structure is solid, tag archives may provide

little unique value beyond what category archives offer. Many SEO practitioners noindex tags by

default.

Alternatively, noindex tags below a content threshold—say, fewer than 5 posts. Once a tag accumulates

meaningful content, allow indexing.

Definitely noindex WordPress date-based archives (monthly, yearly). These provide no topical value

and create many thin pages.

Author archives may or may not warrant indexing depending on your site structure and author

authority. Single-author sites often noindex author archives; multi-author publications may index

them for author branding.

Restructuring Existing Taxonomies

Fixing taxonomy problems on an existing site requires careful planning to preserve any accumulated

SEO value.

Audit Current State

Before changing anything, understand what you have. Export your complete category list with post

counts. Export your tag list with post counts. Sort both by count to identify thin taxonomies.

Identify categories with fewer than 5 posts—these are consolidation candidates. Identify tags with

1-2 posts—these are deletion candidates.

Check for overlapping terms. Do you have both a “WordPress” category and a “WordPress” tag? Similar

names like “Web Design” and “Website Design”? These need consolidation.

Check Google Search Console for indexed taxonomy pages. Are thin archives being indexed? Are tag

pages ranking for anything? Understanding current state guides prioritization.

Migration Process

When consolidating categories, first reassign all posts to the surviving category, then delete the

empty source category. Set up a 301 redirect from the old URL to the new one to preserve any

accumulated link equity.

For tags, if you’re deleting low-content tags, either redirect to a related tag or category, or

simply noindex and eventually delete. Single-post tag pages rarely have external links worth

preserving.

Update internal links referencing old taxonomy URLs. Search your content for links to old category or

tag URLs and update them to new destinations.

After restructuring, monitor Google Search Console for crawl errors and index status changes. Watch

for 404 errors from old URLs that weren’t properly redirected.

Gradual vs. Complete Restructuring

For severe taxonomy problems, you have two approaches. Complete restructuring fixes everything at

once—simpler to manage but higher risk if something goes wrong. Gradual restructuring addresses

problems over time—lower risk but requires sustained attention.

Complete restructuring works well when taxonomy problems are obvious and you can plan carefully.

Gradual works better when you’re uncertain about optimal structure and want to test changes.

Conclusion

Effective WordPress taxonomy requires strategic thinking beyond simple organization. Categories

represent your content pillars and deserve careful planning, limited numbers, and adequate content

volume. Tags complement categories by connecting related content across pillars, but only when used

consistently with a controlled vocabulary.

Regular audits prevent taxonomy sprawl and thin content accumulation. When restructuring, preserve

SEO value through proper redirects and careful migration. The result is a clean, logical content

structure that serves both readers navigating your site and search engines trying to understand your

content focus.

The site with 5 strong categories and 30 consistent tags outperforms the site with 50 empty

categories and 500 orphan tags—every time.

admin

Tech enthusiast and content creator.